The current wave of popularity that surrounds natural hair hasn’t always been at a high.

Especially when it comes to socially acceptability within the black community. There have been tremendous shifts in the ways our African ancestors cared for and styled their kinky textured hair. These coveted practices have changed with the availability–or lack–of traditional products that allow for traditional healthy hair practices or styles.

Back In The Motherland

Whether it be for the increasing the laws of attraction or simply to look stylish, our African ancestors’ ways of hairstyling was as unique as their tribal culture. One common misconception of African hair is the idea that there is one type; this still happens today. Still, there were multiple hair identity types under the umbrella of ethnically classified “black hair”. Tribal-specific hairstyles were signifiers of many societal aspects, such as marital status, ethnic identity, age, religion, wealth, and community rank.

In some African tribes, women with long hair were assumed to have loose sexual morals; in others, it represented insanity.

One of the more important stories that hairstyles served as were markers for geographic location. Through its many commonalities throughout Africa, hair also carried many meanings. A prime example is the message that long, unarranged hair carried. In some tribes, it represented a woman with loose moral; in another it represented insanity. However, the upkeep of hair was not limited to just women. Men of their respective tribes were expected to keep their locs groomed despite the length of their hair.

Dehumanization through slavery

The West African tribes were those most heavily affected by slavery. Through the dehumanization process, captors would cut off their slaves’ hair and took away accessories that were significant to our ancestors’ tribal identities.

For 300 years, the focus of slavery–aside from free labor–was eliminating the attributes that made the African culture beautiful and unique. During this time, due to the denial of traditional essentials such as shea butter, the new generation of slaves adapted. They made due with household and plantation items around them such as bacon fat, kerosene, and butter to lubricate their strands.

The concept of colorism was practiced during this time which brainwashed slaves and modern day African Americans into believing the good hair bad hair craze. Willie Lynch, a slave master in the Caribbean islands, infamously stated that if slaves were separated by color at that time, they would remain separated for years to come. A result of his proclamation was the house slave and the field slave; one being of mixed race with fairer skin and “smoother” hair, while the other was of darker complexion and had kinkier hair.

For preservation of their hair during the long hot days in the field, slaves braided and tied their hair back to prevent dryness from the sun. However, not all slaves had head scarves, which is when grease was applied to the hair and scalp to prevent insects from laying eggs on their scalp.

The “Good Hair” Craze (1900s-1960s”>

With the ideas that there was a specific hair quality that was socially unacceptable and being taught that the natural hair of Africans was less than, Black Americans sought out any possible way to loosen their curl pattern. The multiracial people sometimes had the ability to simply use water to slick their hair back with ease, but many didn’t have that luxury and turned to greater extremes. The hot comb was introduced as a means to help straighten hair.

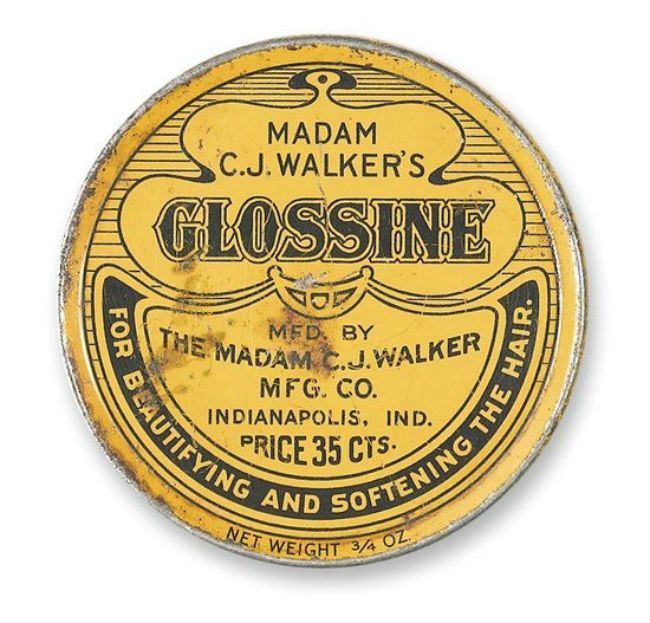

Madame C.J. Walker redesigned the width of the teeth to help those with thicker strands of coarse hair. The Walker Hair System was similar to the preparatory process many naturals go through today. It included using a shampoo and pomade to soften the hair prior to applying heat.

Black consumers wanted an easier way to duplicate their straight hair everyday rather than using a hot comb every time.

Black consumers wanted an easier way to duplicate hairstyles everyday. Men joined on the bandwagon to reinvent their hair, styling it with using the a texturizer created by George E. Johnson. It was called Ultra Wave. Following soon after was a similar product for women to create the perfect waved hairstyle or sleek lightly curled styles.

The Revolution (1970s”>

Prominent leaders of the Black Power Movement were strong believers that black people should be proud of their strong lineage. Angela Davis and Elaine Brown were just a couple of the many Black Panthers who wore their unaltered hair in recognition of their ancestry and defiance of Eurocentric beauty ideals. They encouraged other black people to embrace and appreciate their own natural hair, too. During this time, the afro was worn by everyone from activists to college students.

Jheri Curl Juice (1980s”>

The popularity of the afro was short lived. African Americans still wanted to wear their hair curly but in less of a traditional sense. Now they wanted to have a looser curl that remained moisturized and shiny all day long. With that came the creation of the Jheri Curl. Many people have seen the jokes about the Jheri Curl through popular 80s movies like Coming to America; according to my sources, the elders of my family, keeping the spray bottle was necessary to “keep your Jheri Curl juicy”.

Poetic Justice (1990s”>

Nothing says black hair in the 90s like waist-long box braids that Queen Janet Jackson sported in the film Poetic Justice. This iconic style, commonly used today as a protective style, is not only traditional throughout the African culture but also simplistic in its modern day culture.

A New Wave (2015″>

It’s easy to say that the biggest hair trend amongst the African American community is natural hair today. But there is a twist.

The revival of love for one’s natural hair is astounding. It is significant and, in some ways, is similar to how our early ancestors wore their hair. We wear our unaltered, natural texture in various unique styles. The movement has moved away from using harsh chemicals, decreasing relaxer sales by 26%. At the same time, this has forced major hair companies to manufacture products that will help with the styling a needs of natural hair of every type and texture in order to stay afloat.

Hair trends of the African American community have been adaptations to the circumstances our ancestors were forced to live under. Now is a time that African Americans control the hair market because we’re making our own demands. This is no longer a time where society is trying to impress upon us eurocentric ideas of beauty. We’re defining ourselves.