Urukum

For centuries, the Yawanawa tribe of Brazil has used deep orange urukum pigment to bring harmony to their lands, protect them from evil and purify their bodies and minds. They also have used it to block the sun, keep mosquitos away and to draw intricate geometric patterns on their faces and bodies.

In recent years, Aveda’s Peter Matravers has gone to great lengths to bring urukum — derived from the seeds of a tree indigenous to the area — back to his company’s manufacturing facility in Minnesota to help color red lipsticks and haircare products.

Grown in the foothills of the Andes Mountains, the Brazilian urukum is harvested and the pigment is extracted in raw seed form by the Yawanawa tribe. Then it is transported down the Amazon River to a city where it is trucked across Brazil to Sao Paulo — a distance roughly equivalent to traveling between New York and California.

“It took me 26 hours to get to the destination, and the final approach to their village was an hour-long ride in a hollow canoe,” recalls Matravers, Aveda’s vice president of research and development. “Because it was heavy, we had to bail water out every time we went over rapids, and we had no life preservers. It was very interesting.”

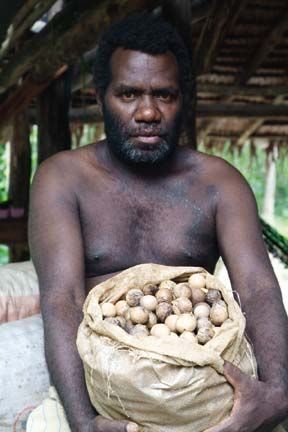

Tamanu oil is derived from nuts, below, harvested by natives peoples on the South Pacific Vanuatu islands. Photo courtesy of Aveda.

In their quest to develop the most effective skin and haircare products, companies like Aveda and Ojon are traveling the globe, turning to indigenous cultures to find ancient tribal remedies. At the same time, these companies want the communities to be a part of their success — a concept called benefit sharing.

“We have a global sourcing person whose primary job is to advise us on novel ingredients with high performance as well as a social aspect,” says Matravers. “Aveda products have to be high performance, and we also need to do something to help people socially and economically while we’re making the product.”

For Aveda, this philosophy can be seen in its travels to the jungles of the Peruvian Amazon to get Morikue from 150-foot-high Brazil nut trees for hair conditioners, which provides 1,000 families of Brazil nut collectors with income and allows them to stay on in their homeland rather than migrating to bigger cities for work. It can be seen in the rose geranium fields of South Africa, where black families have found a way to stay on their land and revive their communities after the devastation of Apartheid. Today, each bottle of Aveda’s Color Conserve Shampoo and Conditioner contains certified organic rose geranium essential oil from one of these South African farms.

And it also can be found in Northeastern Brazil, where traditional communities of babassu women have gathered in the daily ritual of nut-breaking for more than four centuries. Attracted by the quality of the babassu nut oil — which is used in many of Aveda’s hair-care and makeup products — and the sustainability of the women’s craft, Aveda partnered with the babassu women in 1996, helping them earn a living and financing the construction of a babassu processing facility, a soap-making facility and a paper press. With support from Aveda, the babassu women have also created a pharmacy project to produce local plant-based medicines to cure the community’s diseases.

One of Aveda’s most recent discoveries is tamanu oil, which was discovered on the South Pacific Vanuatu islands — a chain of 70 islands scattered across the Coral Sea. Aveda’s global sourcing person noticed that the indigenous people had long, well-controlled curly hair.

“He began asking questions and they began sharing their beauty secrets,” Matravers says.

On the Vanuatu islands — where nobody had ever heard of Aveda — tamanu nuts drop from the tall branches onto the soft sands of the beach. The nuts are processed into an amber-colored oil, which offers intensive moisturizing and soothing properties for hair, skin and scalp.

He brought back the oil, which was sent to Aveda’s investigative research department to look at its functionality and chemistry. A prototype was created and tested against the leading ingredients in the industry to measure its success. In tests, they found that the oil improved curl definition, reduced frizz, moisturized and strengthened the hair.

“It helps us not only confirm what we see on people’s head in a test salon but allows us to quantify the results with numbers,” Matravers says.

The entire process took about three years. In 2006, Aveda debuted tamanu oil with the launch of Damage Remedy Hair and Scalp Renewal and the Outer Peace acne products. It is now found in several Aveda products, including the recently relaunched Be Curly and Hang Straight lines.

“There are many ways of making a curl beautiful, but the Aveda way is probably the most meaningful way because we give back to the community while we’re making the product,” he says.

The tree that produces ojon palm nut oil.

In the case of Ojon, an entire company was built around an indigenous ingredient.

Eight years ago, a relative of Canadian ad executive Denis Simioni brought him a baby jar filled with brown paste she had purchased from an Indian on a Honduras street. He nearly threw it in the garbage, but instead stashed it away in a bathroom cupboard where it remained for two years.

Then one day his wife, Silvana, went searching the bathroom for a product to repair her over-processed tresses. She found the forgotten bottle of paste and cautiously applied it to her hair.

“It totally revived it,” Simioni says. “I couldn’t believe how shiny and soft her hair was.”

Simioni became determined to find more of this miraculous paste made from ojon palm nut oil. Before long, he was on a plane to Honduras on an adventure that would rival something out of an ‘Indiana Jones’ movie, complete with spiders, snakes and sharks.

Ojon Restorative Hair Treatment

A few years and countless trips to to Honduras later, Simioni has built one of the world’s hottest and most unique hair-care companies. Launched in December 2003 with the popular Ojon Restorative Hair Treatment, the company now sells a number of shampoos, conditioners, styling and styling products made with Ojon oil.

With the success of its ojon-based products, the company is tapping the native populations to find new ingredients for its products.

“They have a natural remedy for every beauty concern you could imagine,” Orr says. “That’s basically how he sources everything. He talks to them about their methods and what they’re using. Denis is bringing them to the mass market.”

Ojon’s new Tawaka collection.

For example, one can look at the company’s new Tawaka collection of hair and skin-care products, which contain savage cacao, Alula, Achotie and other rare ingredients native to Honduras. Savage cacao has the anti-oxidant equivalent of 204 pounds of blueberries; Alula leaf is used as an anti-inflammatory as well as to create eye drops to sooth and reduce redness; and Achotie seeds are boiled and used as an antiseptic for skin rashes and snake bites.

Matravers believes that companies like Aveda help the community’s maintain their traditional way of life by creating a sustainable livelihood.

On Vanuatu, for example, Aveda teamed up with Tahitian Prince Ariipaea Salmon, who has worked to provide economic empowerment of his indigenous communities through Pacific Tamanu, a company dedicated to supplying natural plant resources to international markets. As a part of his business, he opened the Vanuatu Convention of Biological Diversity Trust Fund, which is dedicated to raising money for the islands’ schools. Five percent of all sales of tamanu oil are automatically placed into this fund.

“Aveda is trying to give them opportunities that enable them to protect their lifestyle,” he says. “They can supply us with the ingredient we need for mutual benefit.”

Ojon has taken a similar approach in the rainforests of Honduras. Company officials have worked closely with Mopawi, a non-profit group dedicated to promoting sustainable development in the native Miskito and Garifuna populations in La Mosquitia in eastern Honduras.

Mopawi works as an advocate for the Miskito (called “Tawira” in their native language”>, reviewing any proposed development projects, and approving only those that they deem to be in the best interest of the rainforest and its native people.

De Silva is proud of the fact that Ojon pays the Miskito 250 percent of the original market price for ojon oil. In 2004, production totaled 30,000 liters, providing the Miskito with an increase in income of 450 percent benefiting over thousands of people.

The company also set up the Ojon Scholarship Fund to benefit disadvantaged school children in the ojon production area of Rio Kruta and the vicinity. This Fund encourages youth to further their studies and develop leadership skills by giving them access to higher education.

Ojon also holds annual meetings in the rainforest with all of the producers. traveling from village to village to listen to concerns and get updates.

“Denis asks them what they need,” says Ojon spokeswoman Allie Orr. “He wants to preserve their way of life.”